Captain Hook and the case of over-engineering

April 24, 2015

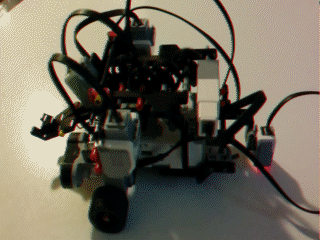

Meet Captain Hook. A week in the making. Late nights. Days off work. Bleary eyes. Finger tips aching from endlessly readjusting bits of plastic, pulling out pins, reconstructing parts that kept falling off. I went to sleep at night stepping through programming loops. I woke up early to scrape through the box of parts. And when I ran out of parts, I broke a rule I set out for all my students by rifling through everyone elses' boxes too.

But the end result was that Captain Hook had everything. Finely tuned gears outputting so much torque to the lifter it could destroy the chassis if sent in the wrong direction. An evasion algorithm so crafty it could lead the robot back to the center of the ring no matter where it started from. It would back out of a duel if it detected it wasn't advancing, it would reposition the lifter if it sensed the opponent had fallen off. It even knew to attack its opponent from the flank. I didn't want to be mean to the kids, but I hoped that by wiping the floor with their crude contraptions in our end-of-term robot sumo competition, Captain Hook would demonstrate several advanced concepts in programming, algorithm design and mechanics.

Instead, they wiped the floor with me.

I had chuckled when one boy used every beam in his box to build an impregnable wall around the front of his robot. Every time he saw what the other teams were planning, he would scuttle back to his own table and add yet more extensions to it, so that it curved and twisted elegantly around every vulnerable part of the robot's undercarraige. The “moustache”, I called it, and undeterred he appropriated the term to name his robot the Mustachioed Destroyer. He was so confident of his design that he didn't blanche as Captain Hook tried to get its lifter underneath the wall. After wearing his attacker down, the Destroyer then fired off his whip, and with a twirl of the moustache, sent Captain Hook flying off the board.

Next up was a tank-bot from the Aboodi-dudes. It's own lifter, I thought, was a valiant effort at Dr. Seuss-like mechanics: endless struts upon struts attempting to support a fulcrum that was essentially suspended in space. Captain Hook's own compact design, tested and refined, would demonstrate Archimedes' boast that with a place to stand, he could flip any wrestler on to its back. Unfortunately, he said nothing about unreliable touch sensors, and my clever trigger mechanism failed to activate. The two opponents locked lifters, but only my enemy's actually lifted. Hook's wheel's spun briefly, and then reversed -- when I wrote the command to do this, I only envisaged the robot backing up for a final triumphant shove, not ignominiously hoisted off the ground -- and was tossed from the ring.

Hammerhead should have been an easy win for me. It's designer had spent so much time building the lethal mallet that pounded in front of it that he hadn't actually finished the program itself. Hence it had no intelligence and just sat in the middle of the ring, smashing the ground repeatedly to no avail. This was perhaps for the best, however. It would have made mincemeat of Captain Hook's delicate frame, built for stealth and cunning, if it had made contact. As it was, the two robots never came close to each other. Captain Hook skirted the ring to make a flanking attack. So far just as I planned, although I was dissapointed that none of the spectators were impressed with my line-following algorithm. They did all laugh, however, when Hook miscalculated the angle to turn back towards the center of the ring. Instead of closing in for the attack, it stepped off the board and into space, losing it's third and final round.

Thus dispatched, the kids pretty much forgot about the robot that had taken me so much effort to build. They continued to pit their own robots against each other, flitting between the ring and the computer to refine their programs. When robotics lost it's hold on their imaginations, several jumped onto the board with pillows under their shirts and started sumo-ing each other. Others kicked a soccer ball around, or shouted jokes to each other, even as a few continued to fiddle with settings and test sensors.

At one point someone called out: “Hey Conrad, can I use your robot?”

“Sure,” I said, “but don't change anything on it.” So! They were impressed with my robot, after all. Perhaps they wanted to admire how sophisticated it is, or reverse engineer its algorithms. I was secretly pleased they wanted to check it out and didn't mind impressing on them just how sophisticated it was.

“It's OK. I won't turn it on,” he responded. “I just want to use it for target practice.”