Muslim missionaries build a utopia among the displaced indigenous of southern Mexico. Their commune looks idyllic, and members say they are content, but neighbours look on with distrust, and this trip inside suggests the missionaries intentions are not all they say.

The Caliphate of San Cristobal de las Casas

first published in Gatopardo on Aug. 19, 2007

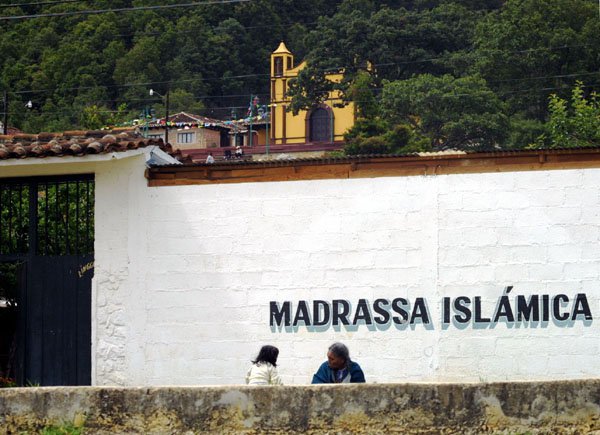

Up in the Sierra Madre mountains of Chiapas, the colonial city of San Cristobal de las Casas is a crossroads of world culture. Rasta-haired hippies from Europe learn Tzotzil, indigenous Tzotzil chat in Tzeltal with their neighbours, mestizo tour companies offer "culturally responsible tours" to indigenous villages, US missionaries build wells alongside the locals. And out on the highway through the Nueva Esperanza neighbourhood reads a simple sign: "There is no god but Allah, and Mohamed is his messenger. Mission for the Da'wa.”

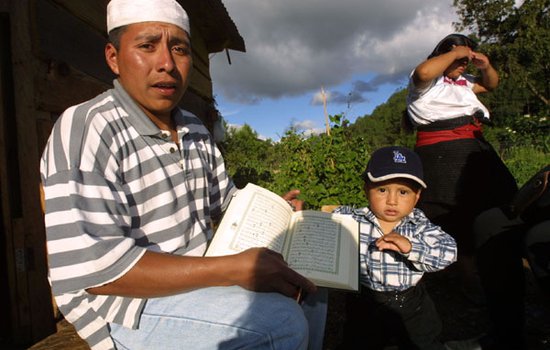

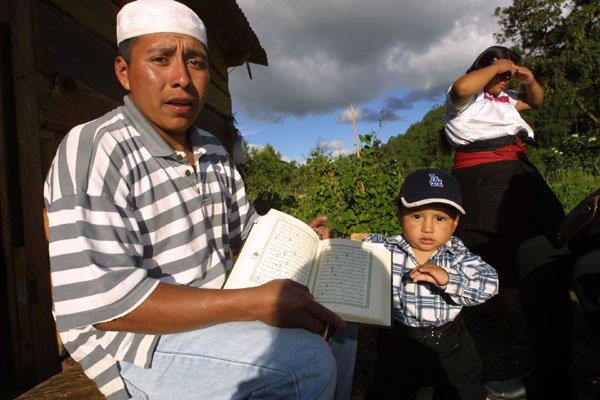

Although it wasn't this sign that caught the attention of Alberto de Jesus Lopez, an unemployed Tzotzil, last month. It was the one next door, tacked onto the side of a furniture workshop. "Carpenters Wanted." It didn't mention the workshop belongs to Chiapas' first Muslim community, that most of the workers are Muslim converts and their bosses are the Spanish missionaries who converted them. But it wouldn't have bothered him anyway. He needed the work. Now, as he rubs sandpaper carefully over a chair leg, he muses that he might convert too. "I like the way they live together. There's a spirit of cooperation and brotherhood.”

If he does convert, Alberto will not only switch religions. He will enter an brazen experiment in social engineering. For the 300 locals - mostly Totzils from Nueva Esperanza, alongside a few Tzeltal, Tojolobal and mestizos - who have gone before him, Islam, the Islam practiced by the Mission for the Da'wa, has meant work, education and a badly needed sense of community. For outsiders, it has meant suspicion and emnity. And for the international organization that backs the Mission, it means, someday, hopefully, the end of the world as we know it.

Like most large properties in the midst of Mexican ghettos, the Mission is a walled compound, 3000 square meters surrounded by crumbling breezeblock houses. Beyond the wall stands a modern well-built carpentry workshop, a sewing workshop, a bakery, a communal kitchen, a tiny school, and the large, airy home of the Mission's leader, Emir Nafia. But there is construction rubble everywhere and it is clear that plans are not yet complete.

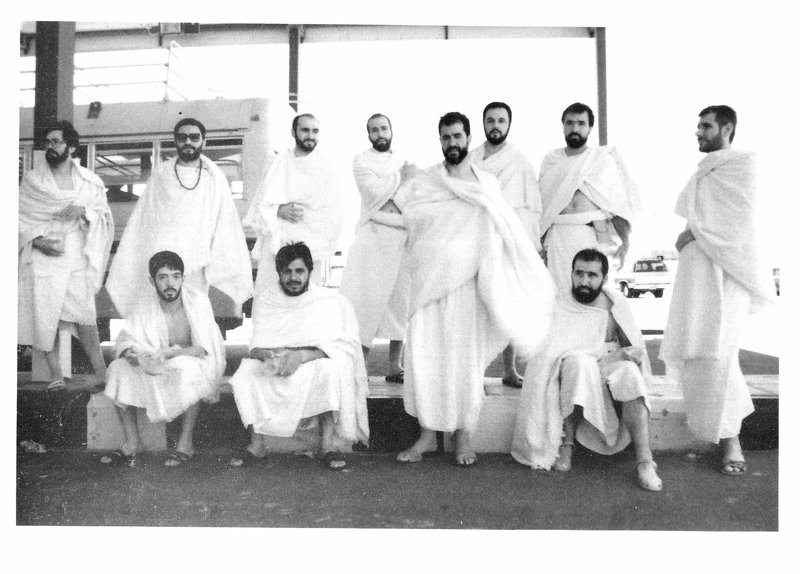

The Mission was founded in the mid-1990s by six middle-class families from Spain. They arrived at the height of social unrest, when long-simmering conflicts over poverty, religion and politics in the state erupted into the Zapatista uprising. A flood of foreign NGOs, activists and missionaries brought aid to the rebel's mountain stronghold, but the Spanish missionaries turned their attention instead to Nueva Esperanza, where refugees from rural conflict had been settling for decades. Instead of struggle, they offered a beguiling form of Sufism, and sustenance. Forty or so families have since joined them, working in the small cottage industries, eating together in a communal kitchen (lots of lamb and whole wheat bread, very little lard or chile) and even sending their children to the Islamic school. Members have taken on Arabic names, their women wear headscarves. Some have even been taken on the yearly hajj to Mecca.

In the carpentry shop, Mustafa Gomez Gomez pushes a board through the band saw. He's been a Muslim for three years now. "It's a 100% better here,” he says, turning off the machine. "I used to be Catholic, but that just brought the easy life of wine and drinking and other vices. Now, there's no booze. I feel much happier with myself, and with my family." Several men in the workshop murmur agreement.

Here, no one shouts, there's no horseplay around the machines, all the tools are stowed where they belong. Shop director Javier Coy, a thin, soft-spoken man from Cordoba, says he has spent years coaxing his men to behave with the dignity of a Muslim.

“We've supressed the two great enemies of society, the labourer and the owner. We've replaced them with the figure of the master and the apprentice.” The workshop is more like a guild than a factory. The apprentices learn the trade, but they also learn courtesy, respect and mutual trust, values which are at the heart of din, the Islamic way of life. And when they have been fully embraced, the apprentices will go off and form their own guilds, thus spreading the din.

I'm impressed, and say so, but I have to know: “How much are they paid?”

“That's not the point”, responds Coy. “No one is here for the salary. They are working for the project, which is much more interesting.”

At 11 o'clock the men break for a snack, gathering either side of a long plank in a garden behind the workshop. The younger ones serve coffee as baskets of baguettes from the Mission's bakery are handed up the table. Afterwards they say a prayer in Arabic, then fall to chatting in their native languages.

One of them is Daoud Abdel Salaam, a Tzotzil of about sixty years old. His Spanish is faltering, but he makes an intense effort to express himself. "It is more correct Muslim. It is knowledge more exact.”

He let's out a sigh. Catholicism, he says, "is a mess."

Daoud and many of the older community members still recall when they fled their homes in nearby San Juan Chamula in the 1970s. Most of them were Protestants, at odds with the wealthy Catholic families that ran the economy, the administration and the police force. Unable to start businesses and living in constant fear of their neighbours, they were eventually driven out at gunpoint. An estimated 25,000 Chamulans became refugees in their own country. It is easy to see why the stability, the surety of the Mission would be so appealing to them.

But children partake of this Pax islamica too. Just up the road from the carpentry shop is the two-storey schoolhouse. Classrooms are well-built and comfortably furnished in a European style. The teachers, mostly Spanish women, are attentive, and the kids hardly stir when a journalist steps into the room. "They have such good hearts," says Aisha Perez, the school's director. “When they came to us they were all dirty. They came to us with their little faces and eyes that said 'what do you bring us?' That said they want to learn”.

On the second floor, children squat cross-legged in lines, boys in front, girls in back, melodically reciting the Koran. The children's faces purse in concentration and the strange phrases flow naturally from their mouths, rushing like waves one open the other. Harmonies ebb and flow. I'm envious.

Outside the walls of the Mission, however, locals are not so content. There's rumours -- entirely unsubstantiated -- of links to Al-Qaeda, of a secret military training camp, of the insufferable arrogance of the converts. The Mexican government has spied on them and led an on-again, off-again campaign to expel them. (I was even followed to the Mission by a state secret service agent on a motorcycle). Even the head of the National Human Rights Commission wondered publicly about the group's motives. "What's behind them?” he asked the press last year. "I do not know."

The roots of a religion

To answer that, we have to head back in time and half way around the world, not to Mecca or the Middle East or even the shining halls of the al-Hambra, but to the incense filled air of London's Soho district, cerca 1975. As the first exiles from Chamula were packing their bags, European youth were on a more spiritual quest. One of the more bizarre destinations was offered by a former BBC scriptwriter from Scotland called Ian Dallas, but also known as Shaykh Abdel Qadir as-Sufi al-Murabit.

Dallas is not an easy figure to pin down. His followers claim his title Shaykh was granted by his Moroccan Sufi tutor, Muhammad Ibd al Habib. Critics say he bestowed it on himself. His current whereabouts vary from South Africa to his mansion home outside Aberdeen. His last public appearance was acting a bit part in Fellini's 8 1/2. (The curious can also see him interviewing the director at the end of Criterion Collection's new DVD release of Juliet of the Spirits). But he is no aescetic hermit, and in the 1970s he preached among radical students and rock stars - Eric Clapton's Layla is based on a Persian poem Dallas reportedly gave to him. Surrender, he told followers in his seductive, theatrical voice. Surrender your ego to the whole, to the brotherhood of Islam. You are but "an imagination of an imagination of an imagination."

It sounds trippy, but there were also some deep political implications. Western governments are hollow shams in the thrall of international finance. The spread of Islam, he demanded, must go hand in hand with the spread of an Islamic political economy and the establishment of a new Caliphate. As the Koran dictates, usury and paper currency will be abolished and when they are, capitalism and the fake democracies it supports will vanish. In its place a new society will rise up, governed not by money but respect, dignity, and good character.

The message appealed mostly to former Marxists, ecologists and other spiritual wanderers. Chief among these were a small group of Spanish leftists, exiles from Franco's dictatorship. The year after Franco died, they headed to Granada to establish the headquarters of Dallas' fledgling organization, the Murabitun Worldwide Movement named for a militaristic Islamic sect of the 11th century.

Today there are only a few thousand Murabitun worldwide, but their reach is broad. They are reported to have communities in more than a dozen counties, including the US, Australia, France, Malaysia, the Caribean, Chechnia and South Africa. There are countless sister organizations - lawyer's associations, bookstores, academies, even an environmental group - that don't always declare their Murabitun affiliation.

In fact, stealth seems to be the strategy. The construction of a $4 million dollar mosque in Granada in 2003, the city's first since the reconquista, made international headlines, but hardly anyone knew it was built by the Murabitun. Similiarly, when the group turned its sights on Mexico in the mid-eighties, they did so quietly. They established groups in Monterrey, Acapulco and Puerto Vallarta, and even built the country's first mosque in Torreon in 1985, all to little fanfare. Yet these were important steps for the movement. "[We] have taken the struggle into the heartland of decadent state-managed Catholicism," a Murabitun brochure from the era boasts: "We are confident the Mexican people will recognize Islam as the new beginning after four hundred years of opression and tyranny."

The emir

I meet Mohamed Nafia, the emir to the Chiapanecan Muslims in the Alpujarra, a pizza restaurant in downtown San Cristobal owned by the Mission. Bearded and heavy-set, Nafia, also known as Aureliano Perez, is courteous, erudite, and notoriously difficult to interview. He dismisses unwanted questions with a wave of his hand, and as he tucks into a tortilla de patatas regales me with accounts of interviews he has walked out on. He won't talk about the Murabitun, or his past, except to say he used to be a Marxist ("I had to cure myself of that") before converting to Islam. He doesn't talk about politics either. He talks like a man of God.

"We think the main problem of the poor in Chiapas is they haven't love for themselves," he says. "Our prophet said purity is a blessing of Allah, but misery is kufr, spiritual darkness. The border between poverty and misery is that, the element of love for yourself."

He hasn't always been so dovelike. Sometime in 1995, Nafia or someone acting for the Murabitun in Mexico, sent a bold and extremely optimistic letter to subcomandante Marcos, who was then holed up in the jungle negotiating a peace agreement with the government. The letter proposed an alliance, or rather an invitation to continue the Zapatista struggle "under the flag of Islam." Together the rebels and the Murabitun would build a new society free of bankers, governments, paper money, and all the other trappings of the exploitative West. Most tellingly, the author offered to stand as a go-between with other rebel groups in places like Kashmir, Chechnia and the Basque region of Spain “with whom we have collaborative relationships of dissemination, guidance and support in their various struggles.”

“Victory or Death!” it ended.

This letter is now in the possession of San Cristobal anthropologist Gaspar Morquecho, author of a detailed study on the Mision para el Da'wa. He says the letter clearly shows the Murabitun came to Chiapas with a "social project” but wonders if the claim to have links with other rebels was just an idle boast. "They may just have been bluffing to impress Marcos," he says.

If so, the gambit didn't work. The Zapatistas never responded, and Nafia was forced to look elsewhere for members. He found fertile ground among the Chamulan exiles of Nueva Esperanza, buying a the property and a cluster of adjacent houses, then inviting neighbours to talks on Islam. He says there was never coercion on their part. "We don't proselytize in the sense that others do. We live our life and when the people come here, we show them how we live and if they think they belong with us they come, and if not they go."

And some did go. In 2000, five families left the Mission after several years, and accused the Spaniards in the local press of extortion and mistreatment. Furious, Nafia accused the media of a campaign of disinformation about the Mission and tried to convince a journalist who reported the accusations to sign a retraction.

The dissidents, meanwhile, formed a separate Muslim community with the support of mainstream Sunnis based near Mexico City.

But the day I visit, everyone looks happy. A group of children shout to each other as they clean out the community swimming pool. Men digging post-holes near the Mission's main wall smile as I pass. They are building a souk, an Islamic market, where the Mission will eventually sell its products. It will be, the Spaniards assure me, much cleaner than the municipal market up the road. And the accepted currency will be gold.

Put your money where your mosque is

Gold, says the website of the Islamic Mint, is the world's most stable currency, paper money is just a promise, like usury. And when that promise is defaulted on, the oppressed of the world get taken for a ride. Gold, or rather gold dinar coins weighing 72 grains of barley - 4.25 grams by today's measure - is also the currency of Islamic law, mandated by the prophet and legal tender under every Caliphate since. In the prophet's day, according to the Mint, a chicken cost one dirham, the silver counterpart to the dinar. Today it still does.

The Islamic Mint, a Murabitun company, churns out dinar and dirham, which you'll soon be able to use at the Nueva Esperanza souk, just as you already can in other Murabitun markets around the world. You may not be able to buy a chicken, but you'll be able to get the batique prints, chocolates, weavings and other knick-knacks that are staple Murabitun products. And for online purchases, there's e-dinar.com. Here, good Muslims can buy and sell with dinar backed by the Murabitun's bullion held in a Dubai safe. As gold-based trade spreads through the world - the Malaysian government has already endorsed such a system for Muslim countries - the usurious financiers of the West will whither away.

But talking about money at the Mission will get you nowhere. I ask Nafia how much it costs to run the Mission.

"The costs are very very very small," he says. "Almost, really, at the present, almost nothing. We are self-sufficient."

I find that hard to believe and tell him so. What with the houses, the vehicles, the woodworking equipment, the school, surely a pizza restaurant and some handmade furniture can't cover it all. “You must have other sources of income.” Before I can finish he has placed his hand angrily over the microphone. His nostrils flare, he rises as if to grab my recorder, sits down, then orders me out. The conversation, and my visit to the Mission, are over.

What is behind them?

Three hundred Tzotzil converted in ten years seems like an inauspicious start to a utopia. But some of the Murabitun's harshest critics say converting people is not what they are really about. “Money, and its growth, are their real concerns, and - without a doubt - their avenue to power,” says Tomas Navarro, a journalist and ex-press officer for the Murabitun in Granada. The converts, he says, are just window dressing. When the Murabitun go on fund raising tours of Muslim countries (principal donors have included the governments of Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, the Sultan of Sharhaj in the United Arab Emirates) they can say they are performing missionary work.

Navarro, and others familiar with the group, insist terrorists from ETA, the Red Brigade and Nuovo Ordine are Murabitun.

But Dallas publicly scorns violent action and if there are any ex-fighters within the group, it is likely they have, like Nafia, "cured themselves," finding in the Murabitun's agenda a more compelling form of struggle than bombs and kidnapping. The middle-class of Europe and the US are littered with violent radicals from the 70s who settled down to get jobs and have kids. Anthropologist Monica Jorba, who studied the Murabitun community in Barcelona, described her subjects as "peaceful and friendly", searching only for "a way to relate to each other.” It would take superhuman cynicism to doubt the sincerity and enthusiasm of people like Coy and Perez.

But if they're not violent, there is something unsettling about them. For all their desire to work with the indigenous, they believe indigenous culture should be repressed. “There are so many things we have to change about them”, Coy told me. “You can stand beside an indigenous person and they smell worse than a dog. Cleanliness is the basis of Islam. You can't pray with a dirty ass.”

Racism is rife within the Murabitun, says Tristano Ajmone, a former member of the group's Italian wing. In South Africa, he says, “they use black Muslims for propaganda purposes and low-level labor. White Murabitun philosophise and give public speeches. But South African Murabitun have done all the hard work, like digging the earth, building villages, minting coins and the like."

Ajmone says that privately, many members profess admiration for Hitler. Dallas has called the Nazi's final solution a “romantic notion.” Many prominent Murabitun in Europe are noted anti-semites.

But it's not just Jews. Dallas and the upper echelons of the Murabitun don't seem to like anyone. The West is the great "enemy," and the kafir, or non-Muslims, are "bloated, fat, pinkish creatures." Arab countries are "islamicly ignorant, (sic)” non-Murabitun Muslims are kept away from their mosques, and the worst of the lot are groups like Al Qaeda. Even before September 11, Dallas was villifying them, in part because their form of Islam is anathema to mystical Sufism, in part because terrorism only affirms the image of the evil Muslim.

Twenty-two year old Ibrahim Chefcheb is one of the Mision's star graduates. Born in San Juan Chamula before his family was expelled, he's been a Muslim since he was 14. He is married to Nafia's daughter, the only local to be granted permission to marry a Spanish female. Despite his slender build he walks with a disarming confidence and stares intensely at his interlocutor. A martial arts teacher, he plans to return to San Juan Chamula to establish a Murabitun karate school.

The self-esteem, he tells me, the "nobility of character", all come from his Muslim faith. Today he looks sadly at his non-muslim friends all hooked on drugs and "a bunch of stuff that are completely outside the good way of life.” And what do they think of him?

“They see me as superior to them,” he answers. “In the good sense of the word. I have good character.”