The accidental fixer

July 24, 2015

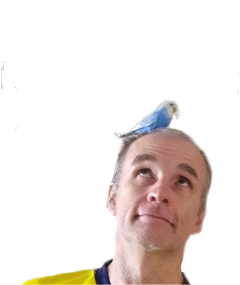

Gaston looks like a rapper gone to seed. He's got the high-riding baseball cap, chunky chain on his neck and saggy jeans. But he also has a pot belly, a scraggly neckbeard and ambles instead of struts through the main square of Tapachula, his home turf for the last three years. He's reluctant to give an interview at first. "It might hurt me with the immigration people," he says, his eyes popping and teeth baring in that peculiarly African way (the only other time he looks animated is when he discusses football). But he takes a deep breath, tells us his life story, and the next day comes back for more.

In fact, everywhere we go, he seems to turn up, gazing at a cell phone in a case made to look like a vodka bottle, one eye glancing every now and again at the pair of earnest journalists at work. He offers to take us to meet other migrants like him, and we accept, shuffling down 8th avenue behind him, stopping every now and again as locals greet him. A group of middle-aged women ask to have their photo taken next to him.

"Where are you from?" they giggle.

"Chiapas", he says.

"Noooo. You can't be. That's impossible. Because of..." They don't want to sound racist. "Because of genetics."

Unsmiling but devilish, he tells them in a thick French accent that there are whole communities of black people living in Chiapas, descendants of African slaves. They listen and murmur and flash their cell phones at him.

We enter restaurants, internet cafes, hotels where other migrants congregate. Everyone knows him. Many smile and stop what they are doing to greet him. Others look resigned, but all acquiesce when he tells them his friends want to interview them.

His approach gets more and more audacious. At first we are just journalists, but then we are journalists fighting for the rights of migrants. Finally, we are from "Reporters San Fronteras", heroes on the vanguard of the migrant struggle. I don't think anyone understands what he means, but they are happy to see someone take an interest in them and grant us open and sincere interviews. For those who are unmoved, Gaston is merciless, insisting and browbeating until we have to step in and reassure his targets they are under no obligations. A pair of Eritreans, young kids in t-shirts and sneakers, nervously explain they have to get to the immigration office. "Some people don't understand we're trying to help them", he says to no one in particular as they leave.

Gaston has a schedule. We're happy to linger at each location but waving his cell phone like a clipboard, he tries to move us along as soon as he judges we've got enough material, reminding us of other places we have to be. By the time we get to the end of the avenue, with several hours of sterling interviews, we realize our interview subject has turned into a fixer. But we treat him to a meal, and he looks genuinely surprised when we offer to pay.